"Horticulture's diversity is also a handicap"

As the science director at the Flanders Research Institute for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (ILVO), Johan Van Huylenbroeck strongly believes in the opportunities that modern breeding techniques can offer to achieve more sustainable plants. Even more so than elsewhere, in the horticultural sector it is important for business and industry and research to join forces in view of the very wide range of products and the complexity. “Even with the latest, fastest breeding techniques, the work is never done. But that’s precisely what makes it fascinating.”

These days, Johan Van Huylenbroeck is used to sitting at the interview table, but above all to determine the skills of job applicants. The Flanders Research Institute for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food in Melle near Ghent is in a growth phase, and in the meantime employs over 650 people. Almost 220 people are part of the ILVO Plant unit. Important research themes at ILVO Plant include healthy soil, plants for the future, plants in a changing climate, sustainable production systems and plant health. The Diagnostic Centre for Plants (DCP) – part of ILVO – also offers support to the sector for analysing bacteria, fungi, mites, insects, viruses and nematodes.

Strong in Flanders and in Europe

Arable crops are a major part of the crops researched, but research into ornamental plants is also an important cornerstone. ILVO has its own breeding programmes for ornamental trees (shrubs and garden roses) and azalea. Within all that breeding research, resistance to disease is an important aspect, but goals can also include hardiness and drought resistance for example. “There are still plenty of testing stations for cultivation research present at home and abroad. Here in Belgium we have the Horticultural Testing Centre (PCS) in Destelbergen. But public horticultural research in the area of genetics and breeding has greatly reduced in Europe. In that area, as the ILVO we are strong in Flanders and even in Europe.” Johan Van Huylenbroeck feels.

A strength and a handicap

Nevertheless there are good reasons why research into genetics and new breeding techniques are important both to the economy and society. If the sustainability requirements for food production are increasing, then that evolution applies at least as much in the horticultural sector too. “The difference is that the horticultural sector is fragmented.” The main arable crops are grown all over the world. So it’s logical that commercial breeders have a view to earning back high investments in research and development due to the scope of the trade in seeds. In horticulture, there is such a wide range of products, even with one grower, that the scale per crop is far lower. For those companies, it is far more difficult to achieve break-even for breeding in such a varied and wide range. The enormous variety in horticulture is a strength, but with an eye to research – and thus to innovation and progress in the cultivars of each ornamental plant – it is to its detriment. “In that way, horticulture’s diversity is also a handicap”, Van Huylenbroeck analyses.

Progress through cooperation

Flemish growers found a response to this by organising themselves in cooperatives. In Azanova, azalea growers look for ways to improve their beloved indoor plant. The cooperative BEST-select develops innovations within the Flemish ornamental tree sector. Successes include the Aiko series of azaleas (new shape of flower and long life) and breakthrough innovations in the Hydrangea paniculate range with the first red (Pinky-Winky) and compact (Bobo) cultivars. The members of the cooperatives help finance the research and in exchange they can obtain the commercial rights to propagate and market them.

Catalyst for more sustainability

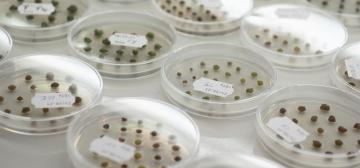

To arrive at these new cultivars, ILVO amongst other things uses bioassays, molecular markers and in vitro breeding techniques such as embryo rescue, breaking breeding barriers and polyploidisation. “It is the modern, specialist techniques that allow us to incorporate the desired characteristics such as resistance to disease, drought or frost into the DNA more quickly than using classic breeding. Roses are an example of a crop that today needs far less (chemical) crop protection than ten or twenty years ago as a result of targeted breeding.” ILVO is currently also working on alternative breeding methods that make it possible to develop more compact plants that require fewer growth regulators. These are examples of how modern breeding techniques can form a catalyst for making the sector more sustainable.

Door still open

“Individual ornamental plant companies often do not have the facilities or the know-how to do this alone, even what we would call large companies in the horticultural sector don’t. Classic breeding has a lower threshold, but especially in crops with a multi-year cultivation cycle, it is a very long-term project. What’s more, you always have to be careful not to cross in any undesired characteristics, that you then later have to cross out again. Using targeted breeding, it is possible to breed more purposefully with modern techniques and thus also become sustainable faster.” That’s why Johan Van Huylenbroeck explicitly hopes that the door has not shut definitively on new techniques such as CRISPR-Cas. They can clearly offer a helping hand in, for example, reducing (chemical) crop protection.

Phased cooperation

Companies always feel an urgency on the market to regularly offer new variants. Research, on the other hand, often takes a longer term view, but has less affinity with commercial practice. That’s why phased cooperation is the key to success according to Van Huylenbroeck. Especially if the joint focus is on making a crop more sustainable, ILVO is a partner. “For us, it is never just about another colour; there must be a higher purpose. We have research projects here that started with project resources that the sector only contributed a small part of. For example, they examine whether a certain technique has potential and whether it is feasible to arrive at concrete results. In a follow-up phase, companies who can see the potential for their crops will participate. After that, they will get to work with it at their own company, on their individual crops, where they will bear the entire cost. Even in this phase we can still be involved by giving advice.” Within ILVO, Living Lab Plant was set up to this end, to facilitate the process of cocreation and knowledge flow to other companies. The end result of such cooperation can be a commercial player with an ecologically and economically interesting product and a research institution that has developed further knowledge, which may or may not lead to scientific publications.

Draw in the consumer

In Flanders, knowledge institutes are aware that cooperation is crucial. Not only between research and the private sector, but also amongst research institutes. Both fundamental and applied practical research are necessary to develop new techniques and establish them in practice. Specifically for the horticultural sector there is the Horticulture Technopole that brings together the province, university, college, research centre and test centre. But maybe the consumer should be drawn in too. “I believe in using less chemicals in horticulture, but I don’t think that it’s possible to have horticulture without chemicals. Especially not if the consumer continues to attach such importance to flawless plants. If the consumer made the mind shift to a slightly greater tolerance for small imperfections, this would facilitate the breeders’ task. Until then we will have to really cherish every link in the chain of integrated crop protection. Making use of natural enemies, but also applying new techniques. We’re no way near having the luxury of being able to rule out new techniques in advance without losing sustainability.”

Box without Calonectria

One of the successful projects that ILVO breeding research was involved in, was the development of box varieties that are resistant to the Calonectria fungus. In 2009, the ILVO in cooperation with the company Herplant in Beerse started to research genetic variation in box varieties. It was then examined how box varieties could be crossed with each other using an embryo rescue step and whether there were sources available that were resistant to Calonectria. Herplant then took up the challenge of starting to cross to achieve a Calonectria-resistant box. In cooperation with ILVO, a bioassay was developed to quickly be able to select seedlings on the basis of resistance. In the last phase, testing and propagating continued at the company. In 2019 a Calonectia-resistant box could be launched at the IPM in Essen. Even with cooperation between the private sector (Herplant) and breeding research (ILVO), it took almost ten years to arrive at a product ready for market. It proves how new techniques can contribute to reducing chemical crop protection, but also how breeding remains long-term work.